Festive greetings from the workshop and well, hasn’t the year flown by?

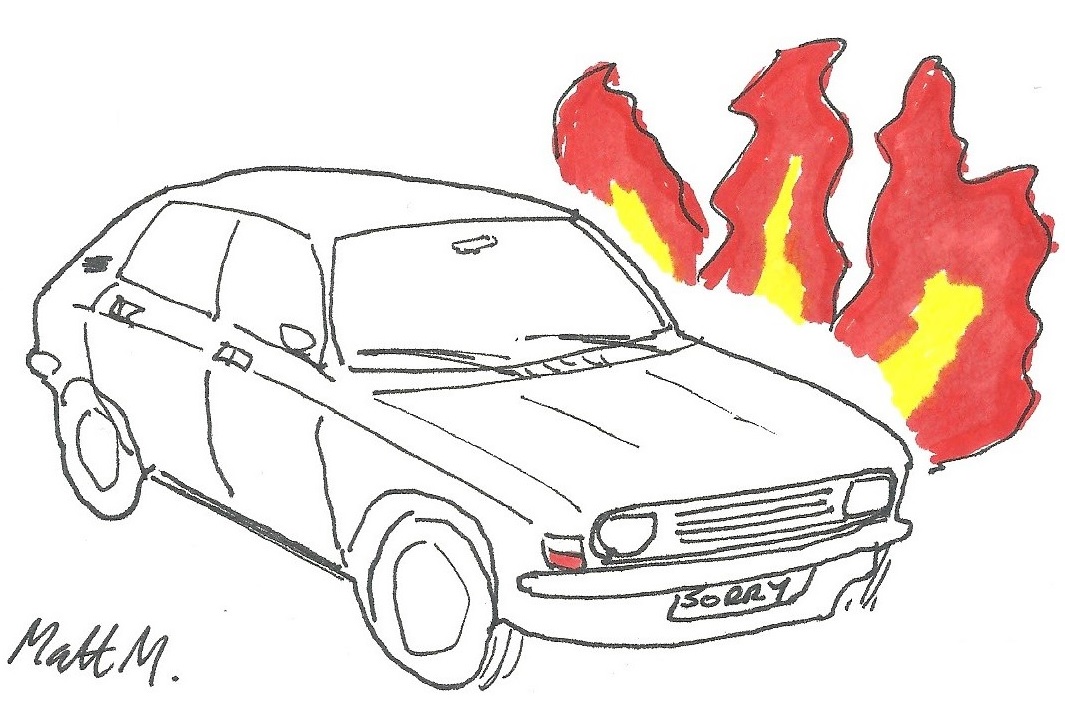

As some of you know already, repair work is a bit of a side-hustle for me, and it’s something I’ve enjoyed since I was a child. Seriously, I would dismantle my parents’ vacuum cleaners, radios, clocks and later, the family car’s engine. Things sort of got out of control when I set fire to my uncles’ Austin Allegro though by muddling up some dashboard wires. Fortunately, the Allegro was made of stronger stuff and survived my handy work, despite a few scorch marks. Anyway, what were they thinking, letting an 8-year-old work on a car unsupervised!

For me, a long-long time ago now, a Fisher Price handyman set turned into Lego building and craft play using old washing up bottles and loo rolls. This turned into blowing up electronics kits, which then moved on to building bikes and cars. As a late teenager, I then got an apprenticeship with BT and studied while I learned about telephone exchanges and communications technologies. All of this might explain why I was never picked for the school team. You can’t have it all, I guess.

Playing with Lego and kits from Tandy (remember them?) for me as a kid definitely helped me to have a positive approach to repair and to not be fearful of getting it wrong. We only really learn from mistakes, of course. And I was lucky to have people around me at the time who were (mainly) happy with me dismantling household things with real tools, taking risks with real appliances and building weird inventions in the kitchen. But it wasn’t all good-humoured in our house! I still remember getting a stern telling off for dismantling a Mini carburettor on the draining board, next to the family’s drying crockery. My mum was upset with me for some reason.

Where’s all this going anyway? Well, as an adult who sometimes acts all grown-up, I’ve since had time to reflect on this maybe unusual set of circumstances, which ultimately lead me to where I am now in Worthing, at 44 years of age. I make no apology for being a pushy parent to my two daughters, encouraging them to create and build stuff; from toilet rolls and sticky tape to their increasing collection of Lego sets, or are they really my Lego sets? I want my kids to learn as I did, the joy of building, testing and usually failing to solve problems. It doesn’t always work like that, but you know what I mean.

I get a wide range of repair enquiries in my inbox, from Kenwood Chef restorations to lamp re-wires to kids’ toy repairs, many enquiries with interesting back-stories too. But sometimes I just can’t take on a repair if I feel that it can be done by the person enquiring. For example, fitting a new plug to an appliance, which I feel, if needed, should be attempted by most folk. The main issue affecting many people, and therefore preventing them from tacking the job themselves, is a lack of confidence. I see it all the time, from vacuum cleaners that just need minor adjustments or cleaning, to lamps that only need a new bulb. When people ask me to do repair work like this, I’ll always give them the option to do the work themselves first, with some guidance – which probably isn’t good for business, but will ultimately help that person to maybe help themselves.

Of course, as adults, there are local repair cafés, DIY college courses and YouTube that can help any budding diy’er, but to be truly repair savvy, I believe that one must start their learning younger and begin through play and the classroom.

In this article, I wanted to share some of my educational thoughts on repair. Appliance repair and general household maintenance isn’t covered as a subject at school (in the UK) to my knowledge, and as we make it to adulthood, we’re just expected to figure it out for ourselves or ask someone else. The closest we get to repair work in secondary school is in Design Technology, but hoover teardowns and rebuilds are not covered. Is this because it’s perceived as unglamorous, basic, simple work, I wonder? Perhaps it’s something I’ll take up with the current Education Secretary, although I’ll have to be quick, as it may all change next week! In all seriousness, our education system needs to encourage practical self-reliance, encompassing repair, if our government is truly serious about sustainability and our environment. In the same way that secondary school mathematics should include topics on mortgages and loan applications, technology subjects should also encompass domestic appliance fault-finding and furniture assembly education, alongside more classical topics so that our children today turn out as adults tomorrow, who can, at least, wire a plug.

Until the next time…