I’m not a fan of batteries. They run out and always when you least expect it.

You know that anything with a battery, will need attention at some point.

Batteries either need to be replaced or better, recharged.

But often, replacement batteries are the only option for toys, which can mean high running costs. Especially when the toy is played with continually by an enthusiastic child owner!

Trouble is, a mixture of built-in obsolescence and poor design means that it’s just not obvious how one replaces duff batteries meaning that, I suspect, lots of toys get thrown away needlessly, but it’s not the owners fault necessarily.

Sadly, some replacement batteries cost more than the toy itself, which is just mad.

Make and model: toy radio control car (no brand or model)

Fault reported: Not working

Cost of replacement: £10ish

Manufacturer support: 0/10

Cost of parts: £5 (batteries)

Hours spent on repair: 30 minutes

Tools needed: Screwdrivers, test meter etc

Sundry items: None

Repair difficulty: 0/10

Cups of tea: 1/2 cup

Biscuits: None

The owner of this toy had played with it non-stop wearing the batteries out. Mum and dad had replaced some of the batteries in the car part of this toy, but still the toy didn’t work. It wasn’t clear to the parents, which batteries in what part of the toy needed to be replaced, which meant that an email asking for help, popped in to my inbox.

At first glance, the car part of the toy had no battery cover or compartment, but on closer inspection, the car separated in to two halves, allowing access to the 4 X AA (1.5V) batteries. Not a straightforward task for everyone. Testing each battery revealed that they were all worn with an average of 1.3 volts (much lower under load) each. I replaced these with fresh ones and put the car back together. The car’s casing was simply held together with a clip and a couple of small screws.

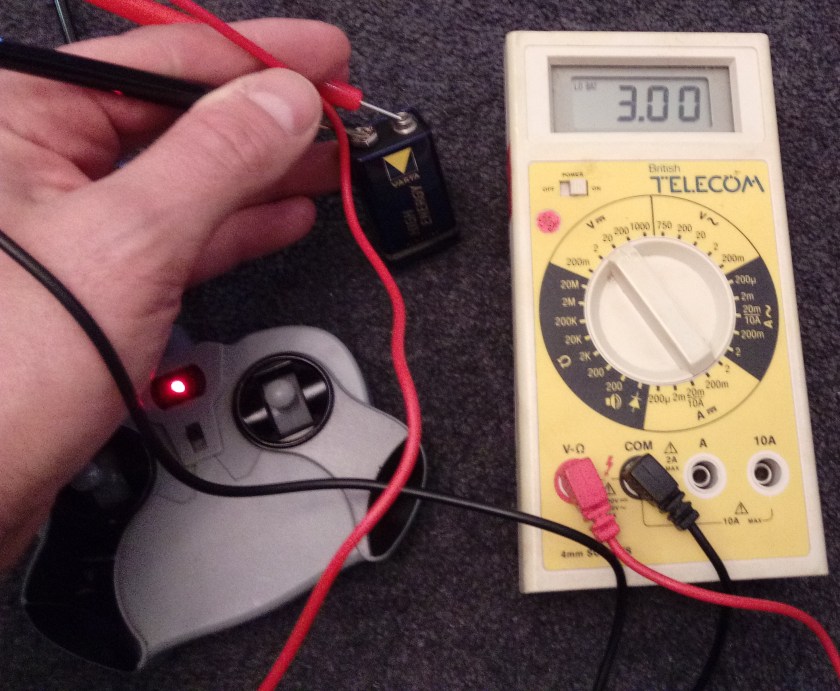

However, the toy still wasn’t working, time to test the radio controller. Again, a screwdriver was needed to open the battery compartment to access the battery. Not all households have screwdrivers (even though I believe they should!).

Testing the 9V PP3/ 6LR61 battery revealed around 3 volts, 6 volts too low. Again, a new battery got the radio controller working once more.

Doing this ‘repair’ got me thinking. Batteries can be tricky things to manage. New ones can go flat when not in use and old ones that have been kicking around in a drawer for a while can be fine to use. One can replace batteries with ‘new’ ones which are no better than the ones fitted, leading a user to believe that the ‘thing’ must be faulty. A false positive.

With a little basic training on multimeter use, hours and cash can be saved by testing pesky batteries. At under £5 for a basic multimeter, it could be money well saved for any household. Just a thought.

With both car and radio controller switched on, the toy sprung to life. Of course, I had to test the car thoroughly before handing it back(!).