Controversy Inside The Workshop

Repair Cafes and campaign groups such as Restart.org and Repair.eu are working hard to defend our repair rights and offer support to local communities, by providing empowering repair skills. It’s all good stuff. But I’m often asked to fix things which are not viable because the damage or wear is so great or the time required to do the fix will take many months, that I can’t offer. And that’s all before we’ve discussed parts availability, cost and other materials. So, this month, I thought I’d consider the case against repair. Have I gone quite mad?

One

Sometimes, it just isn’t worth repairing stuff, sometimes a broken thing should just be thrown out at the appropriate recycling facility, of course… or scavenged for usable spares in my case!

It’s no coincidence that popular TV series The Repair Shop majors on pre-1980 cherished items. Older items, made from quality materials, conceived before manufacturers built-in precise planned mechanical and electronic obsolescence, usually stand a chance of being repaired by crafts people, as that’s how they might have been made in the first place.

You see, a child’s toy or home printer manufactured today, on a sophisticated plastic moulding machine with sealed-in electronics will be almost impossible to repair without destroying the outer casing first. And even if you could get to the faulty battery or printed circuit board, it would be virtually impossible to repair at a reasonable cost, assuming the spares were available. Believe me, I’ve tried. When asked to take on certain repairs, I must be honest and frank with would-be customers about the chances of success and likely time a repair will take, which isn’t a conversation I like having, but it’s essential. Those conversations are not TV friendly.

Years ago, and I generalise here, people repaired things as it was usually cheaper to patch things up to get more wear out of the item. Whether clothing, cars or kettles, repair kits and local engineers were always available and usually cheaper than buying new.

But take a modern washing machine, and parts prices are often not economic to buy, especially when you factor-in an engineer’s time for the repair Its often easier and cheaper to replace the whole thing anyway with next day delivery, just a click away on your phone with interest free credit. And that’s a mighty tempting prospect when the family’s washing is piling up on the floor.

Two

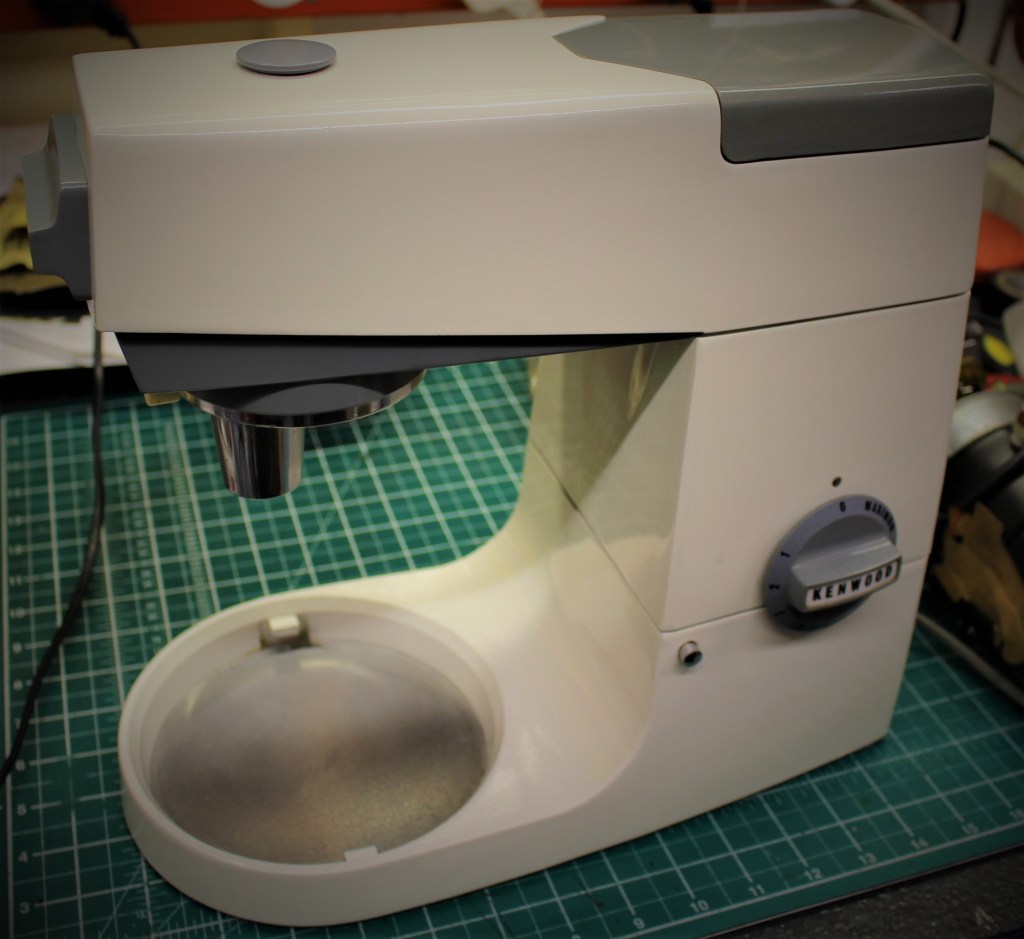

On to my second controversial point; repair is now the reserve of the reasonably well-heeled. As a general observation, most of my customers are reasonably affluent, women coincidentally, and have a historic connection with the faulty item which they want repaired. It could be a favourite family toy or food mixer that needs a little TLC. To bring it back to life, it will need care, parts, experience and (usually lots of) time. All things that must cost money. The results will hopefully bring joy to the customer, which is all part of the experience. It’s why The Repair Shop works so well.

Repair is definitely a discretionary purchase now and if you’re a bit brassic, and your microwave oven goes kaput, are you going to spend £100 getting your old machine repaired? No, you’ll do the sensible thing and buy a new one from Amazon for £40 delivered next day, as you need to feed your family.

Three

New appliances are sometimes more efficient and perform better. Take a domestic fridge. Modern ones could use as much as half the energy than those made 30 years ago, and offer more features as standard.

Compare a modern household torch made recently with one made 15 years ago and it will be like comparing a tea light with the sun. Technology never stops marching on, and we can all benefit from replacing some creaking appliances with something up to date sometimes. But all this comes with a big health warning.

You might be wondering if I’ve lost the plot, knocked the shed down and chucked out my screwdrivers. Not a bit of it. It’s usually more environmentally beneficial to keep something running as long as possible by spreading the manufacturing and shipping impact over a long functional life. And I don’t know about you, but I dislike the thought that someone else has already booked the death day for something I own!

I mean, just by looking at carbon-offsetting alone, consider this: Replacing a domestic kettle every three years, which has been shipped from China, made with complicated materials and electronics with no hope of repair, is not as environmentally kind as a simpler one that lasts for 9 years. Sadly, those kettles just don’t exist any more and if they did, I suspect that they would be far too expensive to be a mass-market product.

It’s such a complicated conundrum to solve, it’s just not possible to do in these hallowed pages alone. But I can leave you with a simple piece of advice; look after your things, buy quality items if you can and consider second-hand at all times to make the Pound (or insert your chosen currency here) in your pocket go further, all very sensible in these uncertain times.

*** Stop press! Feedback from FixIt Clinic in the U.S. ***

One of the great things about keeping a blog is the engagement with readers. Over the years, I’ve built up a network and contact base with fellow fixers, around the world; from all over the U.K., Europe, North America and Australia. We are certainly not alone!

Following my light article on reasons why one might not repair something, my friend Peter Mui from FixIt Clinic in the U.S. got in touch to share his thoughts. I liked his letter so much that I thought I’d share it. And since you’re here and obviously interested in this subject, why not check out their website? http://www.fixitclinic.org

Hi Matt:

I’m compelled to drop everything and to respond to your three cases against repair:

One:

Agreed: many things these days are overly complex relative to their core functionality (the KitchenAid kettle is a good example) and I would totally support a return to simpler designs generally.

Currently there’s a “race to the bottom” where the dominant factor in design for manufacturing (DFM) is to lower manufacturing cost in ways imperceptible to the [purchaser user owner] until the item is out-of-warranty. That’s why Fixit Clinic hosts through colleges and universities: to inform up and coming design and engineering practitioners to design for [durability maintainability serviceability repairability] from the very start using open source designs.

– Totally agreed, Peter. It IS a race to the bottom and agree wholeheartedly with your point – Matt.

How can we get (return?) to a situation where most things can be cost-effectively repaired?

There might be an alternative future where the design and engineering of durable goods discourages “manufacture on sophisticated plastic moulding (sic) machines with sealed-in electronics that are impossible to repair without destroying the outer casing first”, instead: spare parts are readily available at low cost from multiple sources and are easily interchangeable.

Two:

(First: I believe you intended to write “well-heeled” not “well-healed”)

– thanks for the spot Peter – Corrected! – Matt.

Agreed: there’s a component of economic privilege in repair at the moment: ironically it’s more expensive to repair than to buy a replacement.

If the end-consumer / owner is sufficiently motivated to be willing to assume (most of) the research and labor for an item that can often change the calculus in favor of repair; that’s why Fixit Clinic emphasizes conveying generalizable skills over “free” repair or repair as a service. But only the well-heeled have the precious time to undertake repair; your average consumer / average user, factoring in the time and uncertainty of the outcome, makes a reasonable economic calculation against repair and just buys a new item.

Additionally, there’s the perception and widely held assumption that “new” is always better than “used” or “repaired”.

I don’t have a good solution here either: the true full cost of modern durable goods is not reflected in the price paid at the moment of purchase; until the myriad of upstream and downstream costs of an item are added into the moment-of-purchase price this is going to be a hard nut to crack.

Three:

See “They Used To Last 50 Years” https://ryanfinlay.medium.com/they-used-to-last-50-years-c3383ff28a8e which makes the case that if you factor in the embodied energy in their manufacture and their shorter durability, new appliances may not be as ideal as keeping less efficient appliances in service for as long as possible. And I submit that the LED lighting vs. incandescent lighting example is cherry-picked: lighting technology is a category where the energy savings through technology advancement is particularly visible (wink.) The vast majority of new items or features marketed as “advancements” are incremental or even retrograde; my (admittedly also cherry-picked) counter example is 3D TV: do the people who upgraded to pricey 3D TVs feel they got good long-term value? Probably not.

Anyway, thanks for keeping me engaged into the wee hours of the morning.

-Thanks Peter, an engaging response and continuation of the issue. Thanks for sharing the link too. Here it is again for folk who wish to copy/go to the link: https://ryanfinlay.medium.com/they-used-to-last-50-years-c3383ff28a8e -Matt

Your comrade-in-fixing,

Peter Mui @ Fixit Clinic